summit

The Faults in Our Macro Models, and How to Fix Them

During a breakout session at the latest Stanford PACS Philanthropy Innovation Summit, Mike Kubzansky shared a fact that elicited gasps in the room: The Penn Wharton Budget Model, one of the leading tools designed to provide policymakers with accurate analyses of the fiscal impact of various public policies, is based in part on the assumption that immigrant workers produce less than those born in America.

It was clear the math didn’t add up for many in the audience, who hailed from every corner of the globe and had built hugely successful companies and organizations, thanks in part, to the high productivity of immigrant workers. What Mike struck upon in that conversation was just a taste of the myriad hidden mechanisms in which macroeconomic modeling impacts all our lives, often in mind-bending ways.

Omidyar Network CEO Mike Kubzansky speaking on Capitol Hill

The models used by the Congressional Budget Office (CBO) or the Joint Committee on Taxation, along with private efforts like the Penn Wharton Budget Model, are meant to help lawmakers understand the impacts of their proposed policies on things like the labor market, inflation, Gross Domestic Product (GDP), and the federal budget. They can serve as important informational tools, but they also serve an oft underappreciated gatekeeping function: “good scores” can help greenlight a policy, while a “bad score” can doom it to the dustbin of history.

The problem lies in the fact that as the old saying goes, “all models are wrong – some are useful.” The outputs of all models are based on critical assumptions about how the economy works. As a result, whether or not the outputs of those models are useful depends on how close to reality those assumptions are.

Legacy models such as those used by the CBO often lead us astray because the assumptions that drive these complex mathematical exercises are based on outdated research, ignore critical realities about how the economy works, and in some cases, make simplifying assumptions that belie common sense.

For example, existing models underestimate or ignore the productivity benefits of government investment. As a result, they tend to overestimate potential crowding out effects on private investment. In reality, public investment is complementary to private business and can therefore crowd in investment. One need not look any further than the recently passed CHIPS legislation, which has spurred more than $200 billion in private investment.

In addition, legacy macroeconomic models use 10-year budget windows, biasing public understanding of policies that are “good for the economy” as those that demonstrate benefits over the short-run. This short-term outlook overlooks the enormous benefits of other kinds of public investments that are more likely to show up in the data over a 20-30 year window. This means that investments in children, like a childcare infrastructure, universal pre-K, or a Child Tax Credit, are modeled as costly programs without associated benefits because kids don’t become productive members of the labor market until they are adults – something that takes more time than the typical 10-year budget window. Therefore, common sense investments in children are taken off the table as reasonable policy interventions according to conventional modeling.

And then, as Mike pointed out, there are those assumptions that are as shocking as they are incorrect. Because many legacy models assume that worker wages are a direct result of their productivity, the logical conclusion is that “unauthorized immigrants” – by virtue of their lower earnings – must also be less productive. (These assumptions are out in the open on page 26 of a white paper published by Penn Wharton.) As Nick Hanauer writes, “This is stupid and wrong, not to mention racist. While immigrant workers do tend to get paid less than other workers, there is no data whatsoever showing that they produce less. In fact, research even suggests the opposite: that increased immigration is tied to higher employment, higher incomes, and higher productivity.”

The problem is that these errors aren’t just academic, they are a silent engine of economic assumptions, shaping how lawmakers evaluate economic policy proposals and as a result, what economic policies get passed into law. The stakes are high for the future of our economy because the social and economic costs of modeling errors are incredibly high. Critically, the assumptions embedded in existing models aren’t random – they largely tend to bias in favor of outdated, trickle-down policies that result in a chilling effect on policy ideas that champion public investments in the people who keep our economy going.

Groundwork Collaborative Executive Director Dr. Lindsay Owens discusses inflation on “The Problem with Jon Stewart”

We need a new set of tools that are aligned with our growing understanding of economics, social sciences, and human behavior, and take into account critical data points, such as the potential for a given policy to exacerbate wealth and income equality, or alleviate climate change. And like the free market itself, a best-case scenario would include a variety of models to choose from, as opposed to the sparse choices we have available to us today. There should be greater competition in the types of models available.

The good news is that there are new efforts, spearheaded by the Groundwork Collaborative among others, that are working to modernize macromodeling efforts and address some of the longstanding issues that have plagued the field. One such effort, the Institute for Macroeconomic and Policy Analysis (IMPA) based at American University, takes on the flawed tax modeling mentioned above. The IMPA model’s initial analysis of the 2017 Tax Cut and Jobs Act (TCJA) corporate tax provisions revealed that in an economy riddled with rent-seeking, cutting corporate tax rates is in fact contractionary – in direct contrast to what more traditional models found at the time, which was that cutting corporate taxes would be expansionary.

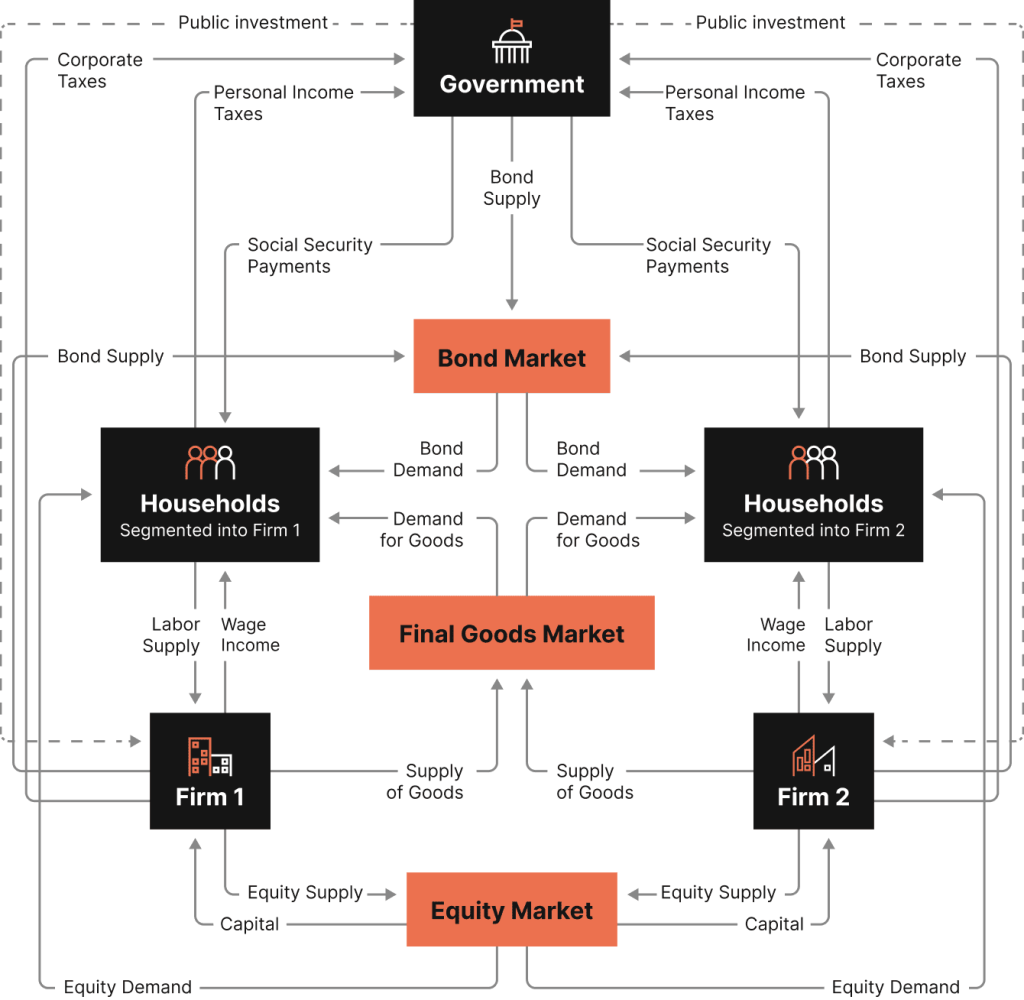

A diagram detailing the main actors and key insights of the IMPA model (source: https://impamodel.org/impa-model/)

This is just one example of how new modeling efforts can offer useful insights into ongoing conversations about tax policy. With a fight over the expiration of the individual tax cuts embedded in the TCJA looming in 2025, new modeling efforts like IMPA will be critical to shaping those debates in a way that results in better policy and a better economy for all.

Building new modeling tools not only provides the opportunity to reshape and energize policy debates in the short-term around issues ranging from tax policy to the need for public investments, they also help us institutionalize a new way of thinking about the economy: one that centers people as the real drivers of economic outcomes and counters stale assumptions about the economy that have plagued our policy discourse for far too long.

Many readers of this publication have been hugely successful in industries like tech and finance, and regularly used models to forecast everything from revenue to capex to inflation to venture growth. So we expect they will understand better than most how valuable a tool these models can be, and the importance of using the most up-to-date and accurate tools and assumptions available to get the best outputs possible. Why use an abacus when we can build a better calculator? No self-respecting VC would ever use 1990 data and assumptions for building their valuation models in 2023. Why should our economy?

Now is the time for leaders in business and philanthropy to reconsider the efficacy of the macro models that we have relied on for so long, and recognize they are not set in stone.

We can make different choices – about the models we rely on, the assumptions built into them, and the policies we pursue as a result.

About the authors:

Lindsay Owens, Ph.D., is the Executive Director of the Groundwork Collaborative. A highly-cited economic sociologist and longtime policy advisor on Capitol Hill, she received her doctorate from Stanford University, where her award-winning dissertation examined the federal policy response to the housing crash during the Great Recession.

Mike Kubzansky is CEO of Omidyar Network, a social change venture that reimagines critical systems, and the ideas that govern them, to build more inclusive and equitable societies. He currently sits on the boards for the US Impact Investing Alliance and the Norrsken Foundation, a Swedish organization that helps entrepreneurs solve the world’s greatest challenges.